Ownership 2.0

Who leads, and who follows?

Editor’s note: As we start a new business year, it seems like a great time to revisit the important topic of ‘who’s gonna do what’. And while the concept of ‘ownership’ is not a new one - not to this blog nor certainly not in general - I thought I’d share an update, with one important addition.

The question.

In my first job at DoorDash I reported to the Regional General Manager of Texas, Dave, who was responsible for that region’s four cities. This largely meant balancing local Dasher supply, restaurant selection, and consumer demand, such that we delivered a great customer experience and hit our monthly growth goals. On that team, I owned Dasher supply, our Sr. Manager of Merchant owned restaurant selection, and Stu, our SF-based Head of Consumer Marketing, owned consumer acquisition.

One Wednesday in March 2017, I remember walking into a meeting room in our Houston office - an office with all the dusty mid-century furniture and flickering light bulbs of a post-apocalyptic video game - as Dave and Stu were in the middle of a white-hot, virtual shouting match. The argument boiled down to Dave’s very reasonable grievance that Stu hadn’t spent that week’s full Texas consumer growth budget, and Stu’s counter that he hadn’t thought it was good ROI to do so. This went back and forth for some time, until, much like the first ripple in the water glass in Jurassic Park, one attendee in the corner of a 20-person Zoom grid un-muted his microphone. It was DoorDash’s COO, Christopher Payne.

The meeting went silent. Pupils dilated. A few attendees went off-camera like French villagers closing their window shutters ahead of a WWII air raid.

“So, I’m listening to you two, and I’m not really hearing an answer, and it’s not looking like we’re going to get to an answer. So I have just one question.”

Time stood still. Birds hushed. Eyes went un-blinked.

“Who owns this?”

Driving ownership.

We all sort of know what ownership looks like in the wild. A colleague burning the midnight oil to hit a deadline. A colleague diving in to manage a crisis. A colleague battling against bureaucracy, in support of a direction they believe is right.

These are good things. We, as leaders, want more of them.

But the reality is that we often struggle to get them. Taking ownership is hard work, and, as such, only our most driven teammates do it naturally. How then, outside of hiring only stone-cold lunatics - a wonderful pipe dream - do great companies drive ownership within their large and growing teams?

The answer lies, I think, in something I’ve realized about the concept itself: ‘ownership’ isn’t a vibe, or a feeling, or a mystical incantation, but rather a set of specific instructions for how we want our people to operate. Said differently, while a few people may occasionally take ownership organically, it’s our job as leaders to drive ownership in every one of our orgs, teams, and teammates.

Ownership Classic™.

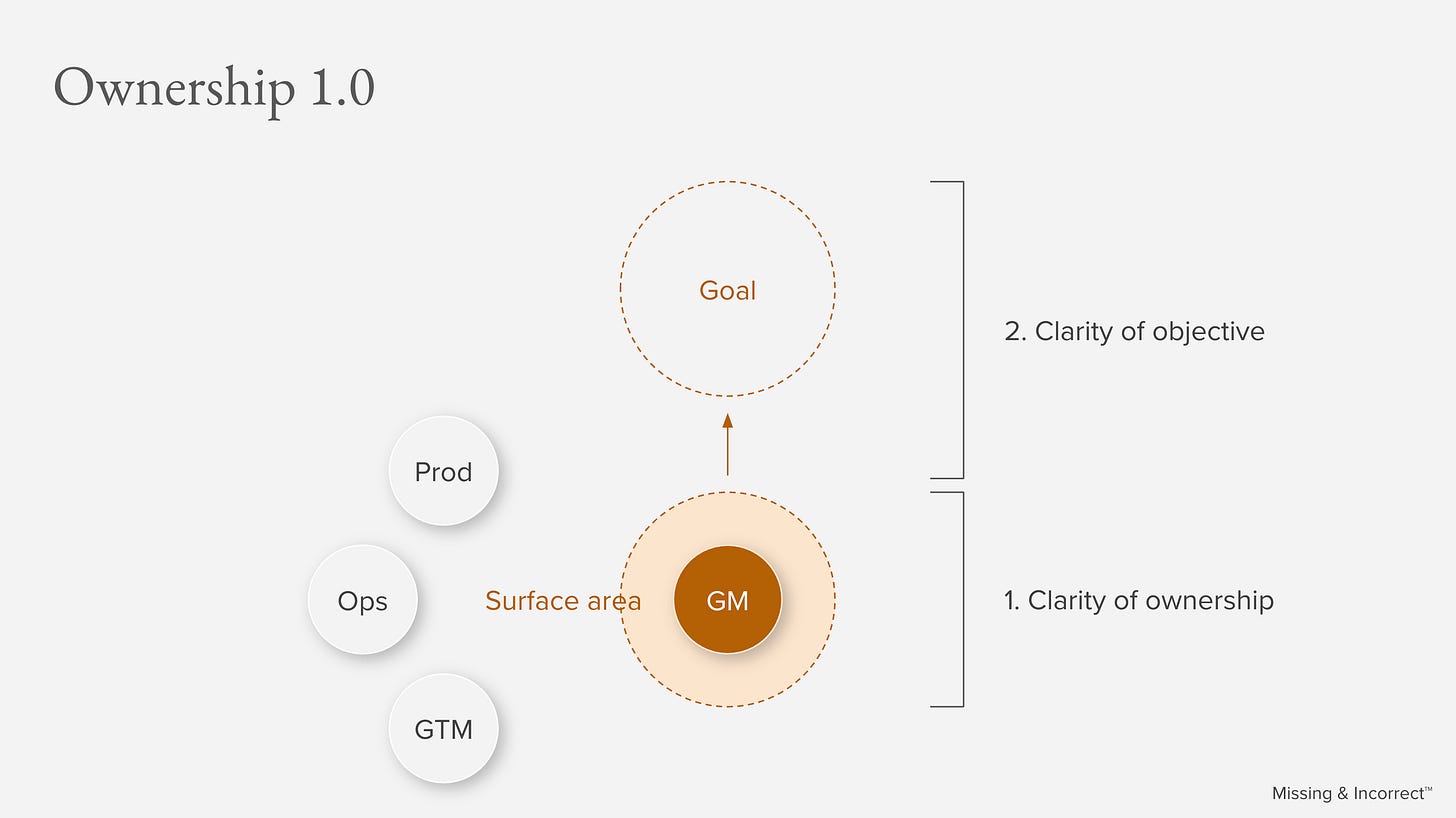

I’ve previously written about ‘ownership’ as having two important parts:

Clarity of ownership: Every business problem requires one owner. Never zero. Never two. Never a team. And certainly never “everyone.” Always just the name of one, human person.

Clarity of objective: Every one of these owners is given clarity on their quantifiable goal for solving their problem, and the timeline on which they need to solve it.

While not Earth-shattering, let’s very briefly recap for those new to the group.

Clarity of ownership.

During DoorDash’s earliest periods of rocket ship growth, I spent most of my Friday nights not watching dreary British crime dramas with my wife, as I’d have preferred, but rather sitting at my kitchen counter bashing away at my laptop. This was because most Friday and Saturday nights, under the weight of our massive growth, our logistics platform would buckle and crash, leaving tens of thousands of in-flight orders stranded somewhere in the North American darkness. And, unfortunately, helping all the resulting hangry, besieged parents, and irate, flour-dusted pizzaiolos, and hustling, ripshit Dashers, was my job.

Because, as Head of Customer Service, recovering bad experiences is what I explicitly owned.

This is a good example of the power of giving clarity of ownership, or defining your company’s jobs not by their tasks, or projects, or skills, but by the business surfaces they each solely own. In this way, there’s perfect clarity on which teammate is keeping watch over each of your critical functions, there’s no wasted time in trying to figure out who’s going to step in to lead in a crisis, and there’s no tug-of-war between multiple people who both think they’re in charge.

Clarity of objective.

So, so many startups treat product management like it’s some kind of otherworldly, supernatural alchemy. That great products emerge serendipitously and randomly, and that the sustained, unending building of stuff is all that’s required to eventually birth a new, inspired, transformational feature.

This is, of course, complete horseshit.

Why do I think so? Because DoorDash, in contrast, very successfully built its products with an incredible amount of intentionality, with most features being designed to solve a specific customer pain point, and attached to a clear success metric. In fact, we eventually developed such discipline as a company that each new release came with both a pre and a post email from our analytics team, the first outlining the A/B test that would measure the feature’s desired impact, and then a second confirming whether or not the feature had delivered it.

I share this anecdote less as a model for product management - one of many areas I know very little about - but more as an example of how rigorous DoorDash was at ensuring that every person in the company was given clarity of objective. That even our product managers, often growth companies’ most mercurial artistes, had measurable goals explicitly defining the impact they were expected to make.

This is a step where founders can err. They incorrectly assume that having given clarity of ownership in assigning the right people to the right problems, that those people will immediately go out and solve them with the white-hot intensity of a thousand suns. In reality, left with an open ended goal of just “make better” and an unbound timeline of “soon,” most people will fail to focus, move too slowly, ship uninspired work, and fail. So, if you’re trying to build, optimize, and ultimately grow your business, each owner must be given crystal clarity of objective: a clear, measurable goal and a specific timeline on which to hit it.

A new, third instruction.

I have realized recently that, much like a two-legged stool, clarity of ownership and clarity of objective are, on their own, insufficient.

No, there’s a missing third piece that brings the concept together.

Imagine a fine dining restaurant. You have a world-renowned executive chef at the helm, whose ludicrously capacious hat signifies that they are the single person at the top of the kitchen brigade. That chef, in turn, has the explicit goal, from the restaurant’s owners, of executing an exceptional menu and ultimately garnering three Michelin stars. Clarity of ownership and clarity of objective to a tee.

However, what chance does Pierre have of achieving this goal, without a group of talented sous-chefs and cooks around him who will, more or less, do exactly what he needs them to do?

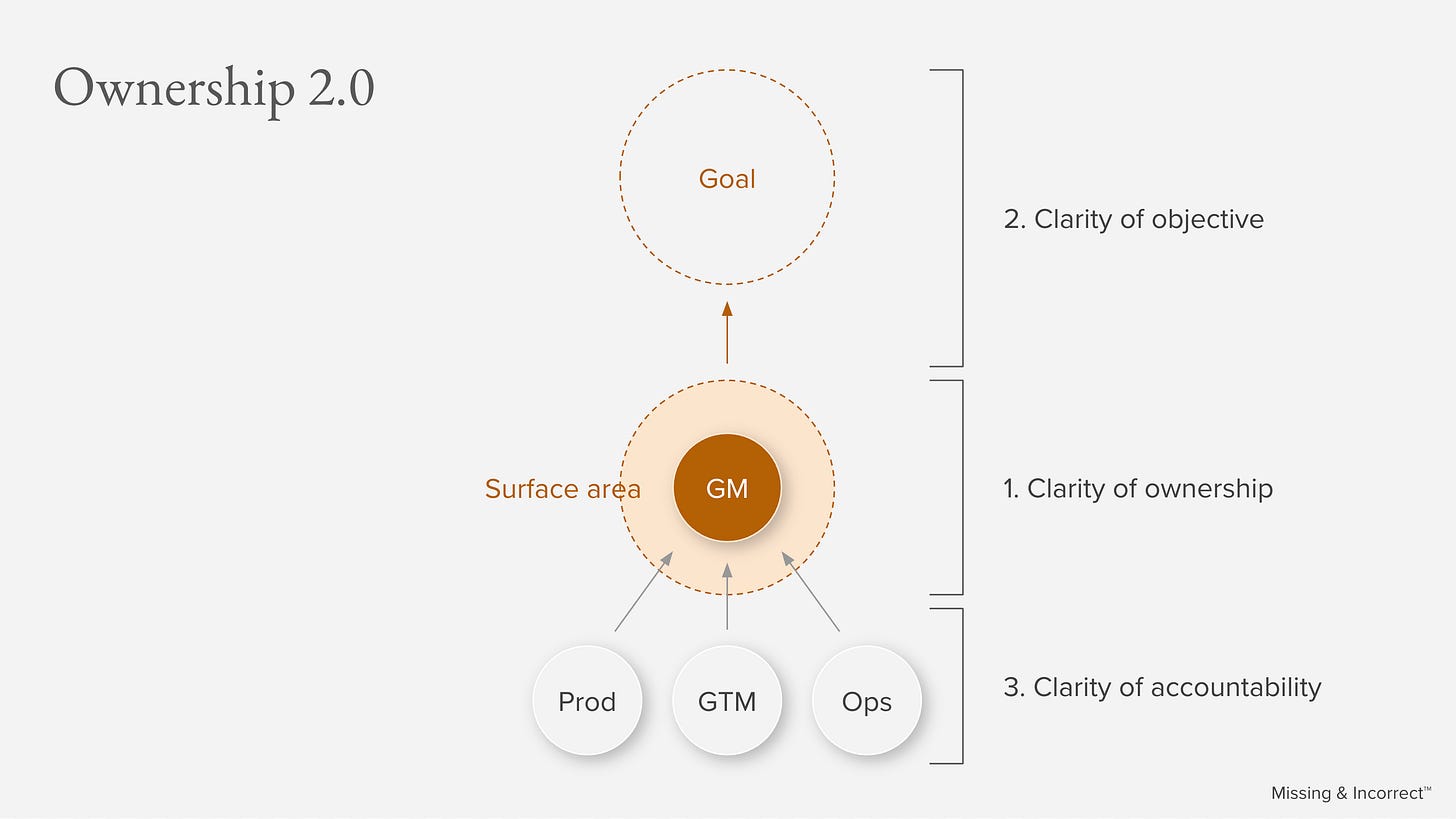

This is the third, critical leg of the ownership stool:

Clarity of accountability. That there is a clear understanding of not just who in the company is expected to own the hitting of a goal, but also who is expected to fall in line to support.

Clarity of accountability.

Most Chief Whatever Officers don’t get to the upper rung of management by being meek, deferential, pushovers. So, it’s perhaps not surprising that, left to their own devices, each imagines that they are completely autonomous actors, empowered to make independent decisions for the betterment of the company. This structure - often known ironically as a ‘functional’ organization - requires an incredibly involved CEO at its center, running the planning and execution motion that keeps each of these executives aligned, collaborating, and generally rowing in the same direction.

Unfortunately, in a lot of growing startups CEOs lack the bandwidth and, oftentimes, inclination to play this role, leaving their executive team running in a dozen different directions at once. This results in misaligned strategic choices, sclerotic decision making, and lethargic, ineffective execution.

Which gets at something I’ve come to believe without much reservation: great companies require some people to lead, and some people to follow. This is why DoorDash built an operating motion that made this clarity of accountability explicit to everyone involved:

It delegated the planning and daily, monthly, and quarterly execution of its business to its COO.

It gave operational GMs clarity of ownership and objective in pursuing the company’s most important goals.

It ran a planning cycle that provided clarity of accountability for every input team - sales, marketing, product, talent, whatever - making clear who they were accountable to, and what deliverables they were accountable for… uh… delivering.

In this way, maximum focus, effort, and resources were put into achieving the company’s goals.

On that note, let’s return to where we left off with my pal Dave.

So, who owns this?

Of the above three ownership legs, Dave had two.

As Regional GM - the single DRI managing DoorDash’s Texas markets - he obviously had clarity of ownership. If there was an unhappy customer, a tropical storm, or a churning restaurant anywhere in the state, it was on Dave to handle it. Dave also had clarity of objective, having been given the concrete goal of growing his region’s monthly order volume by 15% by the end of March. What he wasn’t getting from his partner Stu, however, was clarity of accountability.

To be sure, Stu was right that the ROI of that month’s consumer marketing spend wasn’t going to be great in isolation. Unfortunately, DoorDash’s marketplace runs not on any single input but on the delicate balancing of three: Dasher supply, merchant selection, and, yes, consumer acquisition. In refusing to deploy Dave’s consumer budget, Stu was risking that all the Dashers and restaurants we’d primed for a big weekend would, come Friday evening, find themselves sitting idle, without any orders.

Fortunately, Christopher’s heart-stopping, question reminded all attendees that, in short, Dave was accountable for hitting the goal, and Stu was accountable to Dave. As such, only about 30 minutes later our marketing dollars were unblocked and thousands of 50% off promo cards were urgently dispatched to mailboxes across Texas.

Everyone rows. Even you.

So often in large, growing companies, you’ll get to a point where there are two groups: people who are building and everyone else. Maybe they’re running irrelevant side quests, maybe they’re idly spectating, or heck, they might even be running an active insurrection. But importantly, whatever they’re doing, they’re certainly not helping. DoorDash side-stepped this affliction with the three part ownership model above; 100% of the company’s employees either owned a critical business goal, or were explicitly accountable to someone who did.