“I wanna go fast.” - Ricky Bobby

I don’t know a single growth company that doesn’t have some version of a ‘bias to action’ as one of its core values. “Here at Crüstn, as we revolutionize the B2B frozen lobster distribution space, we move fast and break things.” Love that for you guys.

But what’s more important is what a bias to action means in practice. No question everyone loves the guy slamming Sugar Free Red Bulls, slinging a 90-tab Sheets model with his heart at 280 bpm. But a bias to action is more than just grinding out work, day in, day out. It’s a model of working that prizes action over deliberation. Decision over endless analysis. Iteration over perfection. And, at least in my humble opinion, an enduring bias to action is what separates the companies that win from the ones that don’t.

The slowest companies - think airlines, banks, cable companies - might iterate on a quarterly [or slower] timeline. They’ll bring forward a potential initiative, analyze it into the dirt, workshop it through several dozen VPs, assemble a (God help us) steering committee, and then send it up to the top floor for approval. And in an abundance of fairness, that makes some sense. These are companies that are old, established, and fighting for shavings of market share. It’s the same reason your grandparents aren’t out doing Barry’s; there’s little upside and more likely than not they’re going to slip a disk.

In contrast, growth companies are anything but established. They’re trying to figure out their basic business model, they’re trying to sell a skeptical customer base, they’re constantly breaking already-duct-taped internal processes. Nothing works, everything’s on fire. In that world, when it comes to any decision, who cares? You get it right, you’ve made a quick 1% improvement to something that needs a zillion percent improvement. You get it wrong, what, there’s a tiny bit more fire amongst all the other fire?

So presented here, for your enjoyment, are five steps to actively putting a bias to action into action.

1. The art and science of whoops

To start, just like a vacationing mom who’s already calling the front desk for fresh pillows, let’s everyone just relax. The reality is that in the startup world the vast majority of decisions you’ll make are infinitely reversible. You’ll often hear these referred to as ‘type 2’ decisions, or 2-way doors, where you can pretty quickly Grandpa Simpson your way straight back to where you started if things don’t work out. Launch a new feature? Adjust a customer policy? Change your org structure? Nothing at your very young, fledgling business is so precious you can’t risk wrecking it quickly. In fact, in a world where you’ve figured out so little, the risk of inaction far outweighs the risk of breaking most anything. Make a call, see what happens, roll it back if you have to.

2. Disarm the consultants

Listen, I’m not here to tell you that you, former management consultant, weren’t a John Wick-tier badass for ripping the F1 key off your ThinkPad. Unfortunately, in the often-rugged transition to the startup world, it’s a simple fact that analysis is no longer the end product, it’s a tool to quickly get to a good decision and ideally a great outcome. Thus the importance of running minimum viable analysis.

Good example: you talk to a cross-section of your customers and they tell you, begrudgingly, that they’d generally tolerate a price increase. The question is now how much to raise prices, 12%, 14%, or 16%. Where to start?

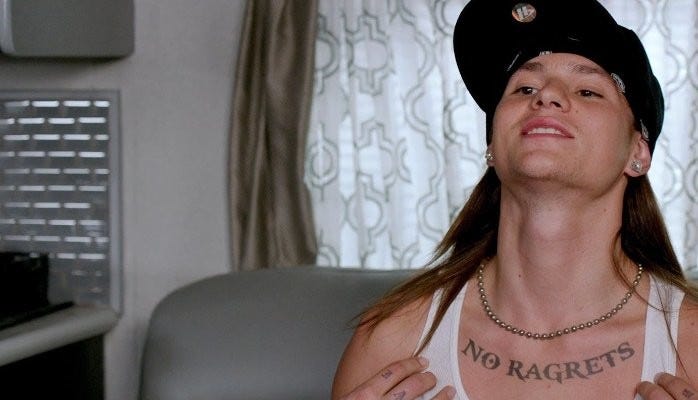

Well, to begin there are eleventy thousand different ways to frame the question. Then you gotta get the right customer insights, run the right simulation to measure price elasticity, ensure you get full cross-functional alignment, and craft the exact right external messaging. Truly, you could spend a half dozen months and put a half dozen McKinsey partners into a half dozen new lake houses without even scratching the surface. And for what? You’re a series A business with $5M in revenue debating a total spread of $200K between your high and low case. Save yourself the time, energy, and brain damage, fire off a 16% price increase to 10% of your customers and move on with your life. No ragrets.

3. I wanna go fast

Few of my DoorDash experiences elicited a bigger ‘you must be shitting me’ than my first invite to a ‘daily stand-up’.

It was the beginning of the COVID pandemic and, as a result of our new status as an indispensable utility, everything had broken1. Orders tripled. Delivery times skyrocketed. Customer service queues were a goat rodeo. Given that situation you could imagine a world where a tiger team would be assembled and asked to report weekly on its progress.2 No ma’am. Instead, the heads of every operations team at the company were invited to a 6pm daily meeting and asked to explain what had happened in the prior 24 hours and what they were going to do to improve in the following 24. And that meeting lasted, best as I can recall, the better part of a year.

While the experience thoroughly sucked, what it did do was a couple things. First, it meant that each week you executed 7 iterations instead of just 1. The upshot there being that you treated every 24 hour window as its own sprint. You got results from the prior day, identified what was working, what wasn’t, distributed marching orders to your team, and sent them off to spend the next 23 hours putting together a better version of what you’d just done.

Second, you can believe it lit a fire under each of us to get our acts together, quickly. Nothing is less fun than showing up to an end of day meeting, in front of your boss, their boss, and all your peers, to tell them you hadn’t achieved what you said you would.

Much to my amazement this process worked. Through the pandemic DoorDash served many millions of new consumers, onboarded tens of thousands of new restaurants, kept hundreds of thousands of Dashers safe and able to continue earning a living, and somehow found a way to keep our global support network up and running. And once the dust had settled and the fires had been put out, the foundation had been laid for what is now DoorDash’s substantial and enduring US market leadership.

4. Get off your ass

Start at the CEO and go down the org chart and you’ll eventually get to the customer-facing people who do the work. Do not be afraid to dive-in and help those people.

In the early days, DoorDash relied on ‘non-partner restaurants’, restaurants you could order from via the DoorDash app but, because the restaurant had no relationship with DoorDash, the order needed to be called in as a take out order by our call center in the Philippines. And, throughout 2018 and 2019, as Friday at 6pm would roll around, that team would get absolutely swamped.

The MBA answer (no disrespect to my people) would be to scrub our forecasting methodology, evaluate the workforce plan, diagnose the gaps, and put a plan in place to return to goal in 4 weeks.

The bias to action answer would be to send a slack to every employee at the company telling them to drop what they’re doing and jump on the order placing tool to start placing orders. And that’s exactly what we did, C-level, VPs, managers, everyone, month after month after month after month. And if I’m being honest, did it make a difference? Sometimes definitely yes but sometimes probably not. But in those latter cases that wasn’t really the point. It was about normalizing a culture where you didn’t just stand by and watch your house burn to the ground, you grabbed a bucket.

5. And what did we learn here today, children

Listen, we’ve had a lot of fun. But the reality is that if you’re running minimum analysis, making quick decisions, and executing fast you are likely to make a few more errors than you might otherwise. In that world you must make it a point to develop a no-blame culture where, when problems crop up, you identify the root cause, share the learnings, and move on. After all, no one is going to wake up motivated to try some new crazy thing the day after having their wrists slapped for doing just that.

Through DoorDash’s massive growth, from basically 2018 on, it felt like every Friday night the app went down. Most often it was because an unexpectedly massive amount of order volume had pushed our infrastructure past its breaking point. However, once or twice, it was because a piece of code was pushed to production when, for any number of reasons, it shouldn’t have.

And this would cause a shit show of epic proportions. Hundreds of thousands of customers wouldn’t get their food, tens of thousands of Dashers would be locked out of the platform, restaurants would have food sitting out getting cold, customer service would get swamped, our refunds budget for a month would be blown. And every time that would happen, our preternaturally composed (and generally rad) head of engineering would calmly ask that the issue get resolved as soon as possible and there be a post-mortem distributed the next day to identify and codify the issue’s root cause. No shouting, no finger pointing, no blame.

So in conclusion, if you take anything away from this post, it’s the importance of getting to ‘good enough’ and movi

More than usual.

Famed anthropologist and noted buzzkill Jane Goodall has suggested that, as tigers are not naturally cooperative animals, tiger teams be renamed ‘chimpanzee teams’. Good for you, Jane. Love that.

Great stuff Steve!

Enjoying your experiences, writing, and metaphors most of all! Kudos.